Algorithmic Remedies

Like any woman with her lifestyle and demographics, she would never have anticipated the diagnosis. Stage 1 breast cancer.

“I was totally blindsided,” admitted Makiko Fliss, a healthy 44-year-old mother of Japanese descent. “I had no family history. I ate well, exercised well.”

But as a pharmaceutical researcher, she figured she would be able to navigate the oncology experience fairly knowledgably. She began browsing around medical websites for information about her particular type of cancer—invasive ductal carcinoma, HER2, ER, and PR positive—but found that most sites were geared toward the medical community, not toward cancer patients and their unique concerns.

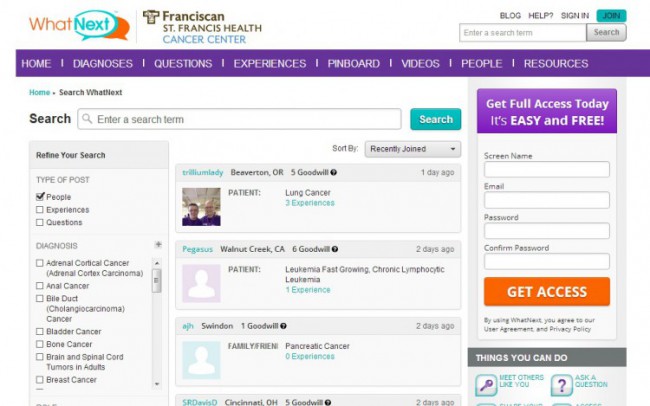

Then Fliss discovered WhatNext.com, an online network created just for cancer patients. Instantly, Fliss began getting real answers to her questions.

Patient Experts

According to a study by Pew, 74 percent of American adults use the internet to find answers about their health. Of internet users, however, only 16 percent get these answers on official hospital or doctor review sites.

According to David Wasilewski, founder of WhatNext, that’s because people prefer to talk to their peers who are dealing with similar issues, rather than a distant medical community. Before 2007, Wasilewski was spending a lot of time trying to find helpful information for family members and friends who were struggling with illnesses, ranging from cancer to eating disorders.

“I was going to the Internet looking for information, and there was just tons of information . . . inspiration quickly turned to frustration,” he said, having experienced hours of research and information overload.

With a background in technology consulting, Wasilewski began investigating how he could make the process simpler. He considered how companies like Amazon and Netflix use robust matching searches to pair customers with products uniquely relevant to them. Could it work with health care also? It was worth a try.

Working with Dan Pickett (now WhatNext’s chief technology officer), Wasilewski developed a proprietary matching algorithm that could connect cancer patients with other patients, information, and resources relevant to their type and stage of cancer, and geographical location. This algorithm sets WhatNext apart from other online cancer communities that Wasilewski compares to cocktail parties. In a typical online cancer community—such as cancercompass.com—like at a cocktail party, people mingle with other cancer sufferers, sharing stories, resources, and information. What happens through WhatNext, however, is that sufferers fast track to the specific members, information, and resources most relevant to them—more like having the host of a party introduce you to particular people who would be most helpful to you.

“Our goal is to make it easier for more people . . . to make better decisions without having to spend hours and hours on the web,” Wasilewski explained.

When Fliss first logged in to WhatNext, she was immediately connected to a moderator—a WhatNext staff member—who directed her questions to particular members who had similar types of breast cancer, and were in comparable stages and treatment programs. Some members were a little further down the cancer journey and could offer her a perspective for the future. For Fliss, that was hope.

“There’s always someone out there listening and someone out there with a similar experience. It’s a tremendous encouragement.”

As a dedicated runner, one of Fliss’ greatest concerns was that cancer would interfere with her physical fitness.

“My biggest fear when I was diagnosed was that I might not be able to run again . . . [WhatNext] immediately connected me to another athlete. She wrote me a huge long letter. She is still an athlete [despite cancer].”

As well, Fliss contacted her acquaintances on WhatNext for advice about preparing for surgery. She already had medical brochures explaining what to bring to the hospital, “but the little things, they don’t tell you.” Little things, like candy, comforting knick knacks, a button-up dress—things only other patients would think of.

In addition to connecting patients with other patients, WhatNext also operates as a for-profit business by recommending particular resources (e.g., local health care providers) to members. In turn, individual providers pay WhatNext to be added to their “go to” list of recommended providers. These providers then directly reach out to members by offering free-of-charge services or consulting, which can ultimately lead to long-term business. Wasilewski calls this service-based marketing, because it offers helpful services to members, marketing to health companies, and a paycheck for him.

In the 15 months since its launch, the network has grown to over 10,000 members. Although they’re small by design, they realize they’ve found a niche.

“People are very interested to share their cancer journeys,” Wasilewski said.

Fast Tracking Transplants

People are also apparently eager to share something even closer to the skin, as Garet Hil found out when his 10-year-old daughter’s kidney failed. Hil, a businessman from New York, targeted every kidney exchange program he knew of, only to come up matchless.

“None of these paired exchange programs were able to find a match for our daughter,” Hil wrote. “Several programs did not even return my many phone calls and some of them wanted to force our daughter to switch to far away hospitals just to enter their exchange program.”

Eventually, Hil’s daughter found a perfect donor in her 23-year-old cousin. But Hil was still frustrated.

“As we struggled through the complex and difficult process of finding a compatible donor, it was clear to me that there was a better way.”

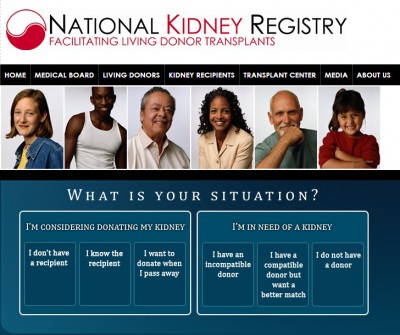

So he came to the same conclusion as Wasilewski—if something needed to be done, he was going to have to do it. And the National Kidney Registry (NKR) was born.

So he came to the same conclusion as Wasilewski—if something needed to be done, he was going to have to do it. And the National Kidney Registry (NKR) was born.

Based on matching software similar to WhatNext’s tool, NKR pooled together all of the kidney registries in the U.S., creating one giant pool of donors and recipients, hugely expanding the possible matches. The first year—2008—NKR facilitated 21 matches. Then 62 in 2009, and 130 in 2010.

NKR has also facilitated six antigen match transplants, typically a rarity accounting for just one percent of all kidney transplants. Those who receive a kidney from those with an exact antigen match tend to live longer than those who don’t.

Perhaps one of NKR’s most notable successes are the numerous match chains it has generated. A chain is created when a “Good Samaritan” (a donor who with no family or friends needing a kidney transplant) donates their kidney to a recipient whose family member or friend then donates their kidney to another recipient, and on in on. The longest chain kicked off by NKR involved a total of 22 people. Initiated by “Good Samaritan” Christina Do, a 36-year-old from New York City, 11 people received new kidneys in seven months.

“Donating a kidney wouldn’t really change my life, but it could save someone else’s. I couldn’t think of a good reason not to do it,” she told Glamour magazine in an article about kidney chains.

To date, NKR has facilitated 389 transplants, with an average wait time of 8 months (the industry average wait time is 51 months).

Groups like WhatNext and NKR might be anomalies in the world of health, but it’s likely they have a future. Wasilewski thinks that WhatNext’s matching equations could be used to connect people with a variety of different diseases. Perhaps next on the horizon, networks for those battling Alzheimer’s or Multiple Sclerosis.